An Analysis of Economic Trends in U.S. Music Industry Capitals: 1995-2003, with Implications for Music Industry Education

Frederick J. Taylor Georgia State University

Introduction

The record industry is reported to be experiencing a downturn in the sale of its products. Mix magazine’s recent special report, “What Can Save The Music Industry,” is reflective of a growing number of published articles from industry insiders and observers over the past three years predicting the downturn. The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), National Association of Recording Merchandisers (NARM), Video Software Dealers Association (VSDA), and the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) indicate that the recording industry, both domestic and foreign, has experienced significant declines in record sales over the last three years. RIAA reported that the overall size of the recording industry based on manufacturer shipments at suggested retail prices decreased from $14.323 billion (2000), to $13.74 billion (2001), to $12.614 billion (2002), to $11.854 billion in 2003. (RIAA Statistical Report, 2003)

In one of the Mix magazine articles, RIAA claimed that a 26% decline in record sales from 2000 to 2003 had occurred primarily due to file sharing of recorded product over the Internet by high school and college students (Jackson, 2003). NARM, RIAA, and IFPI reported significant declines in recorded product sales from 2000-2003. In an attempt to reverse the perceived economic downturn of their industry, the RIAA enacted what some would consider desperate measures. In various news outlets, periodic reports of possible charges brought against minors for music copyright violations (Internet file swapping) with the RIAA holding parents financially liable for their children’s malfeasance and seeking damages, often in excess of ten thousand dollars per occurrence, have been observed. Media commentary of these events often portrays the RIAA as a group of big businesses ruining the lives of children and their parents.

An additional area of concern for the record industry is the less-than-stable business climate of the broadcast industry. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) relaxation of guidelines for radio station ownership and programming content are upsetting the traditional business environment that the record labels and radio broadcasting conglomerates have previously enjoyed (Clark, 2003). Congressional challenges to recent FCC regulations may also serve to perpetuate caution by record labels as to where, and with whom, to invest promotional dollars. Due to the aforementioned, label executives are claiming that the glory days of the record industry, commonly perceived to be the mid-1990s, have passed and will be replaced by an era noted for a declining number of labels destined for eventual extinction (Jackson, 2003). Label executives are also predicting that a domino effect from shrinking record sales will negatively impact other sectors of the music industry as well (Franklin, 2003). For example, when record labels cannot afford to adequately finance their star acts or emerging artists, an inevitable dampening of the creative and entrepreneurial climate in the label-supported fields of recording, publishing, songwriting, video production, and concert promotion will become a reality.

Is the music industry experiencing a downturn, or perhaps a business or technological restructuring cycle? A proper examination of this question should begin with a consideration of whether the record industry has ever encountered such dramatic challenges to its existence in the past. The history of the record industry will provide the context for this discussion. A brief review of extant scholarly analysis on the history of the U.S. music industry, and its economic impact, is contained in the following section.

Review of Literature

Relatively few scholars have chosen to examine the history and economic impact of an industry as large as the record industry. It must be noted, however, that numerous books, magazines, and articles have been published about this industry which have not been subject to scholarly review. Nevertheless, sufficient literature exists to provide historical context for this examination.

The first known treatise on the history of the record industry, From Tin Foil to Stereo—Evolution of the Phonograph, was published in the 1950s (Read & Welch, 1959). As the title suggests, the authors’ focus was to trace the technological advancements within the recording industry. Information concerning the early years of the record business depicted a fledgling in-dustry struggling to survive in the midst of technological advancements. Read and Welch’s (1959) research was shown to have inspired subsequent works by authors such as Schicke (1974) and Gelatt (1977).

A decade later, Malone (1968) published a comprehensive history of country music which included a more detailed reading of the development of the business side of the record industry. He identified the birth of the record industry in 1890 and traced its development through the mid-1960s. Of particular interest to this study is his explanation of the periodic economic downturns within the record industry. For example, Malone explained that the introduction of radio in 1920 became the major factor in the drastic decline in record sales during the 1920s and showed that a later label alliance with the radio industry served to dramatically increase record sales beginning in the 1950s. The author’s description of such external factors as the U.S. government’s rationing of vinyl and the musicians’ boycott during World War II provide cogent insight into the periodic fluctuations the record industry has faced throughout its history.

In the 1970s, interest from consumers of popular music as well as industry observers fueled the publication of numerous books and articles on the various aspects of the record industry—a trend which persists to this day. Information ranging from anecdotal (exemplified in the legendary record mogul Clive Davis biography of 1975) to hard data from the RIAA contained in industry trade publications such as Billboard became ubiquitous. However, the researcher is faced with the daunting task of ferreting out reliable data from the hyperbole in this body of literature.

The era of music industry scholarship began in the 1980s and was exemplified in the doctoral dissertations of Shore (1983) and Shea (1990). Shore expanded on the previous work of Malone (1968) by providing extensive analysis of the business and economic trends of the record industry from its birth to the late 1970s. The researcher’s numerous tables, containing RIAA yearly dollar and unit data (circa 1899-1978) of record sales, provided strong support for his detailed and frank analysis of the industry. Of particular interest to this study was Shore’s account of record industry economic trends in the late 1970s. He explained that

…industry executives began to look forward to the days when the sale of five million copies of a record would be a regular occurrence. This unbridled optimism was severely shaken by the downturn that hit the industry in 1979.

Within quite a short period of time the industry’s song of limitless horizons changed to one of controlled gloom. (Shore, p. 144)

More importantly, Shore’s conclusions for the aforementioned industry downturn of 1979, specifically poor performance of the U.S. economy combined with escalating shipping costs and promotional budgets, bear a striking resemblance to current record industry claims cited in the 2003 Mix articles.

The research of Shea, though focused on the impact of technological developments in popular music, includes a substantial body of material on business and economic trends within the record industry. Neglecting to acknowledge Shore in his work, Shea’s dissertation contained a number of similar data points to the aforementioned and drew similar conclusions. However, Shea did provide an interesting history of the competition between record labels showing how adoption of new technology—e.g., turntable speed, stereo recording, etc.—by one label tends to force adoption of similar technology by competing labels through capturing increased market share. However, the importance of Shea’s research, as it relates to the present study, is primarily found in his conclusions and recommendations. He identified and linked the principal of industrial inertia to the record industry and demonstrated that most of the impetus for change had historically come from forces external to the industry.

The 1990s saw the publication of research from academics in the relatively new discipline called music industry studies. Initially, the focus of this research was to provide, in textbook form, general information on various aspects of the music industry. The works of Baskerville (1990), Wadhams (1990), Fink (1996), and Hall & Taylor (1996) are examples of the aforementioned that examined—in varying degrees of depth—subjects such as record industry history, business practices, and economic trends. Baskerville’s, Wadhams’, and Fink’s textbooks provided comparatively limited data and analysis of industry business trends due possibly to the texts’ foci. The Hall & Taylor textbook provided a more in-depth analysis of business and economic trends of the record industry.

The research of Taylor & Terrell (2003) is the first known quantita-tive/comparative analysis of economic and business indicators on domestic music industry capitals. Among the salient findings of this research are indications that the traditional dominance of the music industry by New York, Los Angeles, and Nashville are waning. Emerging capitals of music industry commerce, such as Atlanta, demonstrate an emerging pattern of industry decentralization.

The body of literature indicates that the record industry, and its perceived support services—operationally defined in this study as the music industry—have experienced the following:

1) periods of dramatic business and economic downturns

throughout its history; 2) downturns often caused by external environmental factors; 3) challenges to change its perceived static business state;

and 4) patterns of possible decentralization among its traditional industry capitals.

To determine the viability of the currently perceived music industry downturn, a longitudinal analysis of industry business and economic activity was performed. A description of the data collection procedures and methodology are contained in the following section.

Methodology

This study explores what recording industry insiders and observers have claimed: that the record industry has fallen from a pinnacle of economic boom in the mid-1990s to experience an increasing decline in sales from 2000 to 2003. The purpose of this study is to determine what evidence, if any, of these reported business and economic trends can be found among five U.S. music industry capitals. To this end, a longitudinal analysis was performed using data selected from various industry and government databases on the five domestic music industry capitals of New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Nashville, and Atlanta for the years 1995, 2000, and 2003. Nine music industry sectors were selected for comparative analysis to determine individual strengths of the selected music industry sectors in each city for the selected years. The nine music industry sectors are:

1) recording studios

2) artists and entertainment managers or agents

3) entertainers and entertainment groups

4) record and prerecorded product outlets 5) musical instrument stores

6) musical instrument manufacturers/wholesalers

7) licensing, royalties, and publishing services

8) creative services

9) broadcasting services

The databases used in this study included the 1997 North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) CD-Rom, the 2000 U.S. Census Report, and databases from Dunn and Bradstreet for 1995, 2000, and 2003. The Dunn and Bradstreet databases contained data on over 11 million U.S. business entities and are considered to include 89 percent of the total domestic business population (Stormant, 2000). The NAICS database was used to identify and group music industry sectors by Statistical Index Codes (SIC) into the nine industry sectors of the study. The 2000 U.S. Census Report was used to determine geographical boundaries of the five cities under review. The authors loaded the Dunn and Bradstreet database with the selected SIC numbers—separated by city, year, sector, and geographical parameters—for analysis. The findings of this study are presented in the results section.

Limitation of this Study

For the sake of clarity, the scope of this study is limited to nine predetermined music industry categories. Among the music industry categories not included are business entities whose products or services are experiencing significant market declines, such as hi-fi and other acoustic equipment manufacturer/wholesaler and services. Support services such as audio cassette duplication services, musical instrument rental services, music education instruction, and sound and lighting equipment rental are likewise not included due to lack of significant market share. Finally, two of the most significant growth sectors for the music industry—entertainment legal services and web-based music delivery entities—are not included, due to current limitations in the NAICS eight-digit protocols which tend to overstate activity within these sectors.

Therefore, the results of this study cannot be generalized to encompass all music industry activity for the cities under review. Additionally, because only five music industry capitals were included in this study, the data and results of this study cannot be generalized to reflect accurately music industry business and economic trends for the entire United States.

Results

The purpose of this study is to measure the various business and economic trends of five music industry capitals to determine the extent of the reported economic downturn in the record industry. The results of this study indicate that:

1) despite a significant slowing of growth rate in revenues, the five cities as a group showed positive growth through the eight-year period in the three measured categories; 2) despite declining recording sales, the other industry sectors were found to be in various levels of economic well being; and 3) there is strong evidence of decentralization in the music industry.

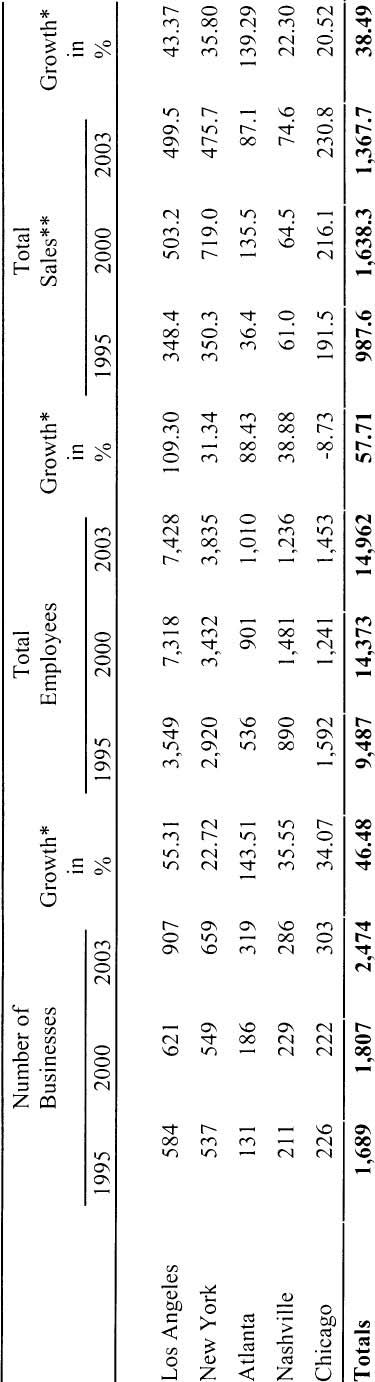

Table 1 indicates that Los Angeles is the traditional leader of the five cities in the commercial recording studio sector for all three categories (number of businesses, number of employees, and total sales) with the exception of New York showing the most sales in 2000. The data also indicate that during the eight-year period New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Nashville, and Atlanta, as a group, experienced a positive growth of 38.49% in total sales, however, negative growth was shown to have occurred from 2000 to 2003 in Los Angeles, New York, and Atlanta. Nevertheless, the five cities, as a group, had positive growth in the categories of number of businesses and number of employees during this eight-year period. Finally, Atlanta experienced the largest percentage growth in number of businesses (143.51%) and total sales (139.29%) during this period of study.

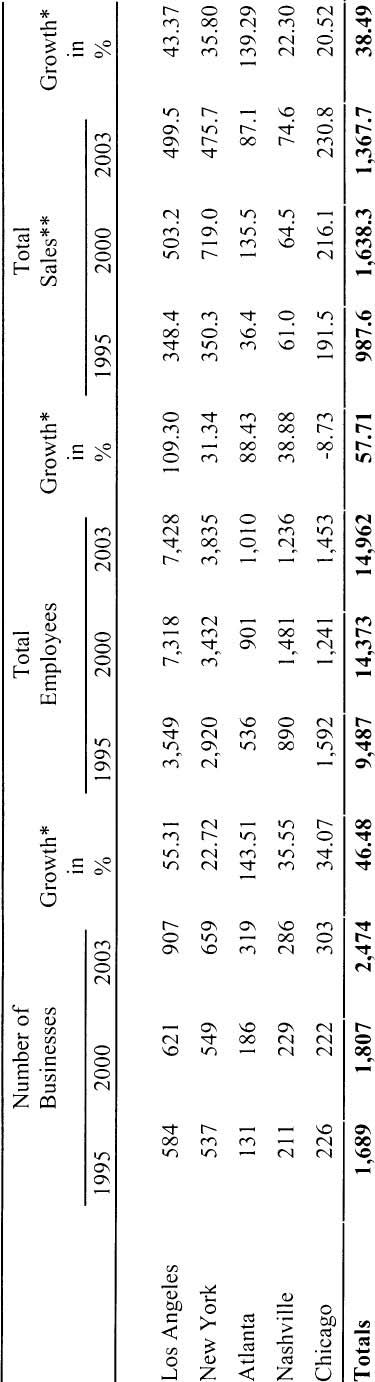

The figures for artist agents and managers found in table 2 indicate that these business entities did not fare as well as the recording studios, exhibiting only a 19.86% growth in total sales for the period. New York, the leader in all three categories for the period, experienced negative growth in number of employees and uneven growth in number of businesses. Additionally, New York’s sporadic growth in number of businesses and number of employees and Los Angeles’ negative growth (-12.39%) in total sales for the period contrasts the robust growth of the other cities in this industry sector. Finally, Atlanta was shown to have experienced the largest percentage growth in all three categories for the group.

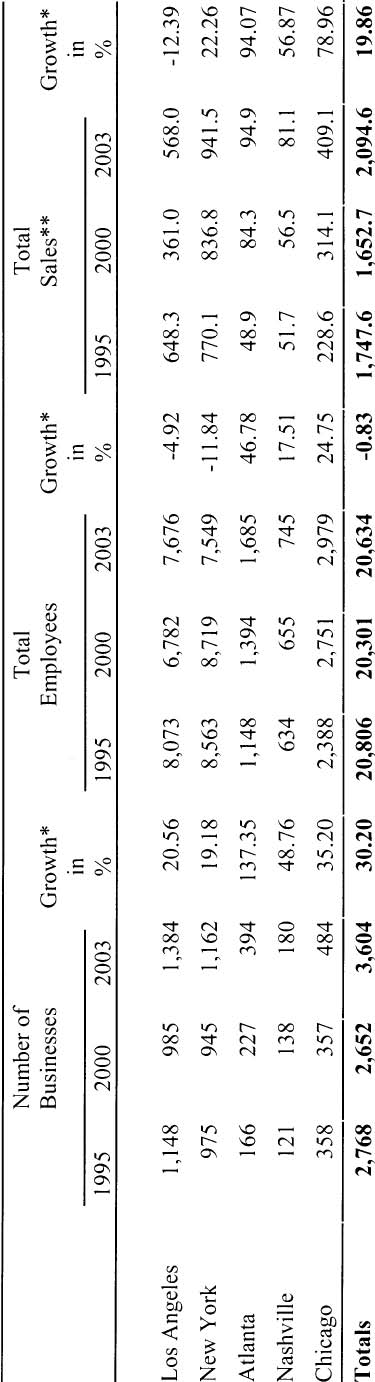

Table 3 indicates that the sector of live entertainment has experienced significant positive growth over the past eight years. The totals for five cities show an increase in all three measured categories including a 47.98% growth in total sales and a 103.1% gain in number of businesses (e.g., bands, orchestras, etc.) for the period. New York is the preeminent city in this industry sector with Los Angeles and Chicago losing market share to Atlanta (ranked second in total sales for 2003) during this eight-year period. Additionally, Atlanta generated the largest total sales in 2000 and the largest percentage-growth increase in all three categories for the eight-year period.

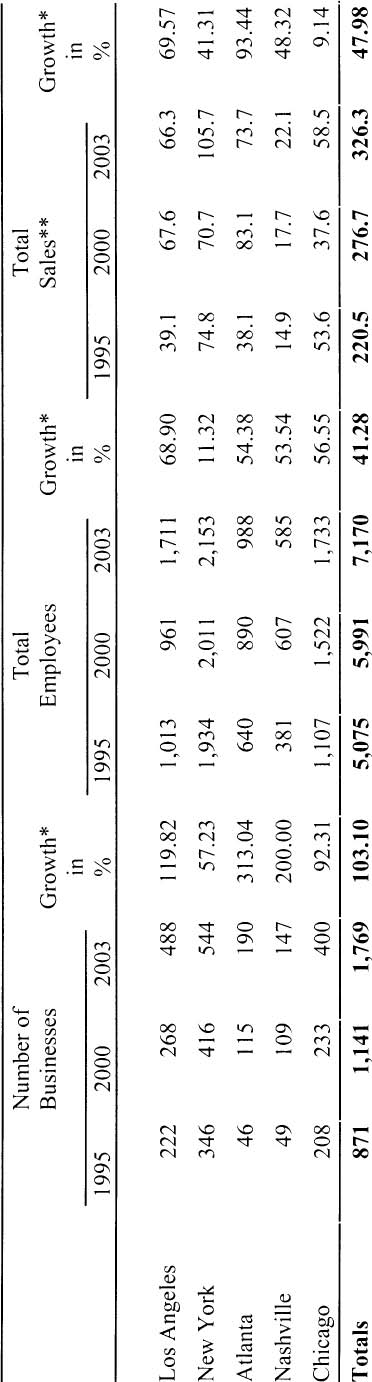

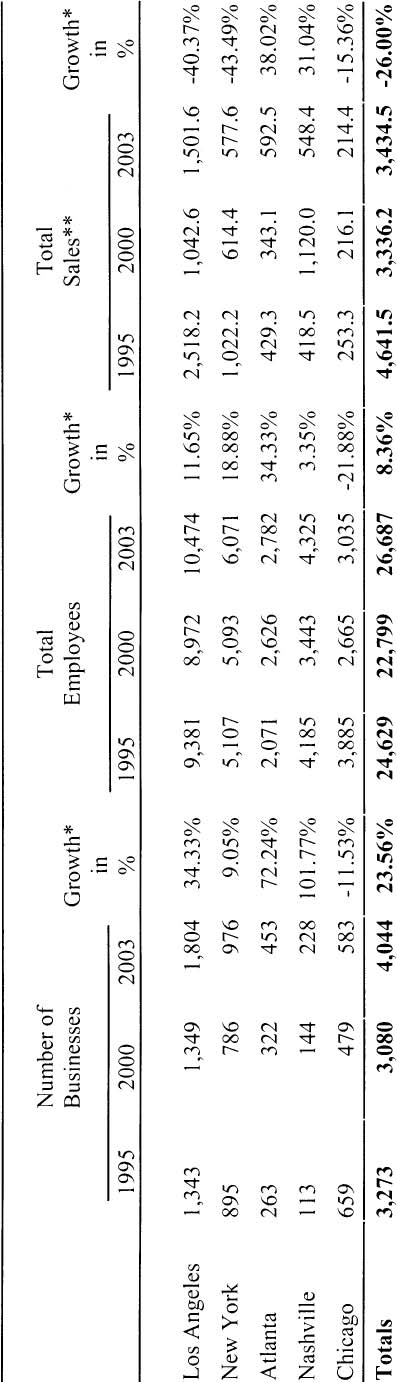

The totals listed in table 4 seem to reflect the Recording Industry Association of America’s (RIAA) claim of a negative growth (-26%) in record sales from 2000 to 2003 (Jackson, 2003). The retail record outlets of the five cities under study recorded a 26% decrease in total sales over the eight-year period making this the weakest of the nine sectors under review. However, a closer examination of the data shows that the five capitals, as a group, experienced the greatest losses in all three categories between 1995 and 2000. Therefore, a more complex explanation than the RIAA claim of Internet file sharing may be needed given that file sharing did not reach significant volume until after 2000.

Los Angeles, the traditional leader in all three categories, has expanded in both number of businesses (33.34%) and number of employees (11.65%), but lost significantly in sales (-40.37%) over the past eight years. New York’s percentage growth was nearly equivalent to Los Angeles for the businesses and employees categories, but it lost enough total sales (-43.49%) to be surpassed by Atlanta in 2003. The figures for Chicago indicate a smaller but nevertheless negative growth pattern for the eight-year period of -15.36% in total sales. Nashville experienced robust growth from 1995 to 2000 only to lose over half of its gains in total sales receipts by 2003. Despite a negative growth period in total sales from 1995 to 2000, Atlanta showed steady growth in both number of businesses and number of employees during this period of study. Atlanta also experienced the largest percentage growth of the five cities in both number of employees (34.33%) and total sales (38.02%) and ranked second in total sales in 2003.

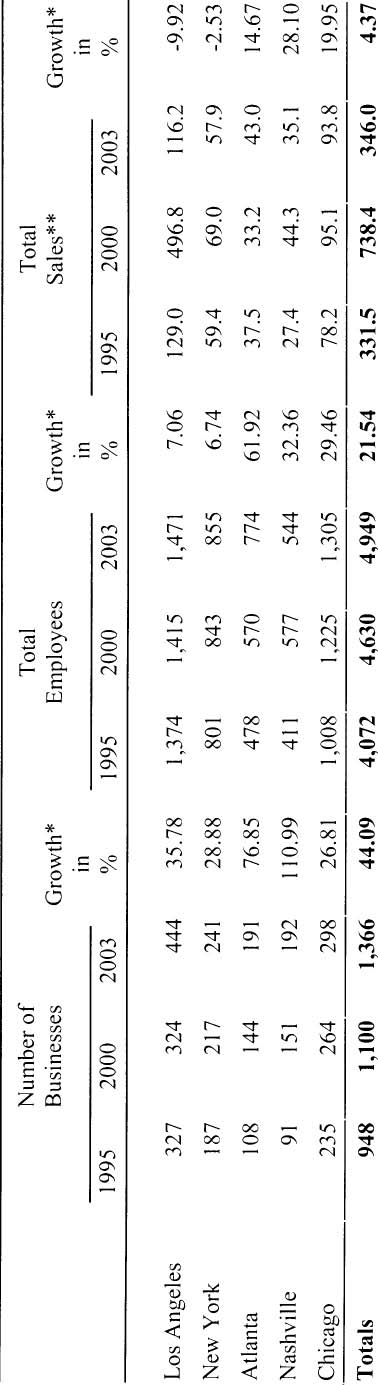

Table 5 contains the data for retail musical instrument stores. The figures indicate that this industry sector is less than robust. The totals for the five cities indicate that the growth in number of businesses (44.09%) and number of employees (21.54%) has significantly outstripped total sales (4.37%) over the eight-year period. Additionally, the cities, as a group, lost over half their total sales from 2000 to 2003. This sector was found to be the second weakest of the nine measured industry sectors of this study.

Los Angeles, traditionally the preeminent center for music retail, has lost 9.92% in total sales over the last eight years and seen its sales plummet from nearly $500 million in 2000 to $116 million in 2003. This city’s apparent predicament, compounded by a 35.78% growth in number of music stores and a 7.06% increase in number of employees during the past eight years, may make it difficult for it to maintain its position as a leader in this category. Chicago, ranked as the strong second in all three categories, was found to be less volatile than Los Angeles, losing less than $3 million in sales from 2000 to 2003. However, Chicago’s approximately 30% growth in number of businesses and employees may be problematic in the face of a less than 20% growth in sales receipts for this period.

The figures for Atlanta and Nashville, ranked fourth and fifth respectively in all three categories, indicate a more positive economic picture than the other music capitals. These two cities share the largest percentage growth in businesses, employees, and sales of the group. It is noteworthy that only Atlanta experienced positive growth from 2000 to 2003 in all measured categories of musical instrument retail.

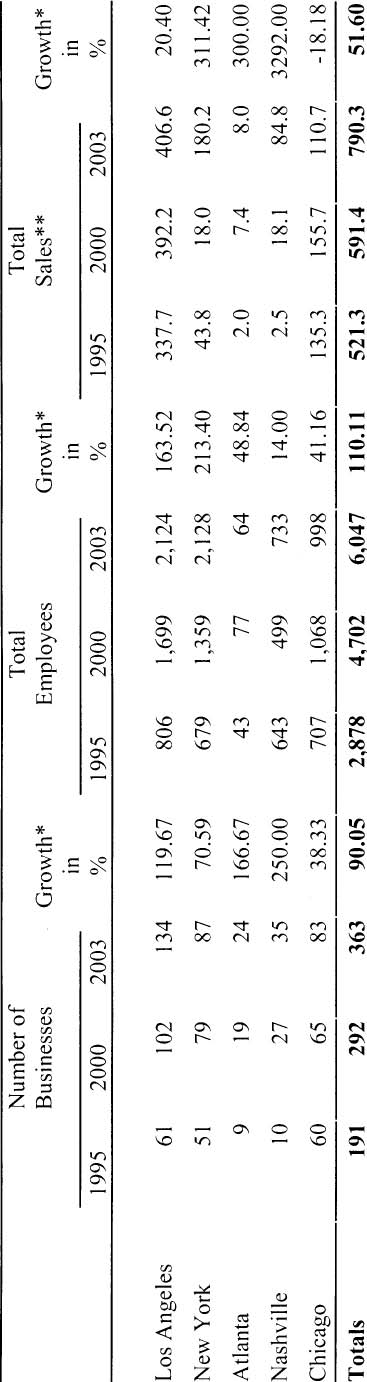

Although musical instrument retail was found to be a generally weak sector among the music industry capitals, table 6 indicates that the musical instrument manufacturers and wholesalers are faring much better. The cities recorded steady growth in all three categories: 90.05% growth in number of businesses, 110.11% increase in number of employees, and a 51.6% increase in total sales for the eight-year period. Los Angeles is the dominant city in all three categories, boasting total sales that surpass the sum total of the other four cities throughout the eight years of this study. Chicago, traditionally ranked second in this sector, lost a sufficient amount in total sales (-18.18%) to be surpassed in this category by New York which had a tenfold increase in sales from 2000 to 2003.

Nashville, emerging from a distant fourth place ranking, is in position to possibly challenge Chicago in this sector. Nashville’s music manufacturing and wholesale sector boasts a 250% increase in number of businesses and a 3,292% increase in total sales for the period; these figures represent the largest percentage growth for an individual city found in this study. Atlanta’s steady growth in businesses and sales, though impressive, was nevertheless unable to budge the city from its current distant last place ranking for this sector.

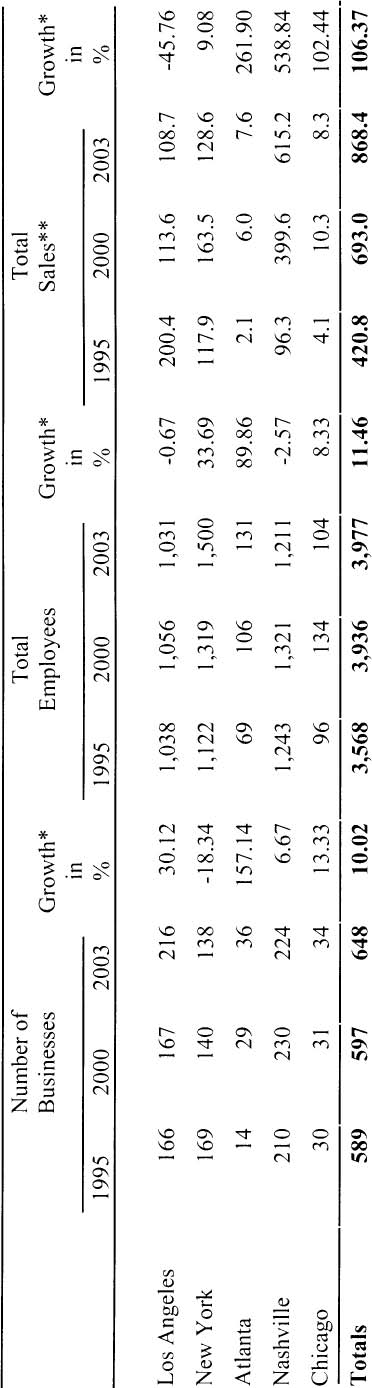

Table 7 contains the data for licensing, royalties, and publishing services. Despite a less than impressive growth in number of businesses (10.02%) and number of employees (11.46%), the cities experienced a 106.37% increase in total sales for the eight-year period giving this sector the largest percentage growth found in this study.

Los Angeles, the leader of this sector in 1995 lost over 45% of its sales receipts in the ensuing years. New York showed negative growth in this sector from 2000 to 2003. Chicago and Atlanta, ranking a distant fourth and fifth respectively across all three categories, had the largest percentage increases in number of businesses and number of employees. However, their combined total dollar output is only about 2% of the total sales for the five cities.

The preeminent city for this sector is Nashville. From 1995 to 2000, Nashville moved from a third place ranking to first place in all three categories. A more remarkable statistic is Nashville’s total dollar output in 2000 and 2003, which surpasses the other four cities combined. This is strong evidence of the decentralization of the music industry among the five cities.

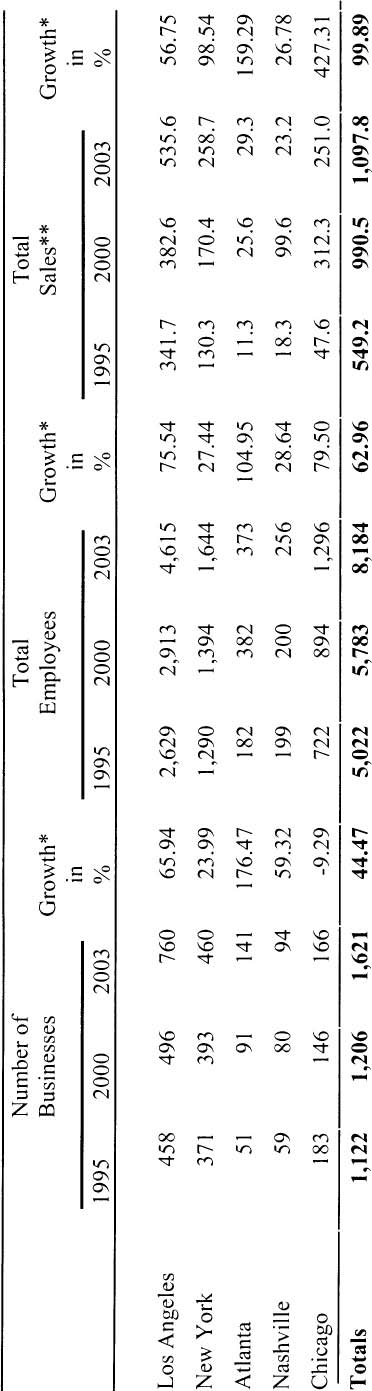

The fields of songwriting, music arranging and composing, music video production, and disk reproduction were, for the purpose of this study, included in the sector entitled creative services (table 8). The totals for the group indicate that this sector is thriving, exhibiting positive growth in all three categories. The positive growth in number of businesses (44.47%) and number of employees (62.96%) is outpaced by the group’s growth in total sales (99.89%). However, an examination of the data from individual cities indicates mixed results.

Los Angeles is the leading city throughout the eight-year period in all three categories. Additionally, Los Angeles accounts for almost half of the total output, businesses, and employees of these five cities. New York and Chicago exchanged positions in the second and third place rankings from 2000 to 2003. Nevertheless Chicago, which occupied a distant third place position in 1995, experienced sufficient gains in total sales to garner the largest percentage growth in dollar output (427.31%).

Atlanta and Nashville, ranked fourth and fifth respectively, experienced positive growth throughout the eight-year period. Nashville experienced a significant decline in sales receipts from 2000 to 2003. However, Atlanta experienced steady growth in all three categories throughout the period and registered the largest percentage growth in number of businesses (176.47%) and number of employees (104.95%) of the five cities.

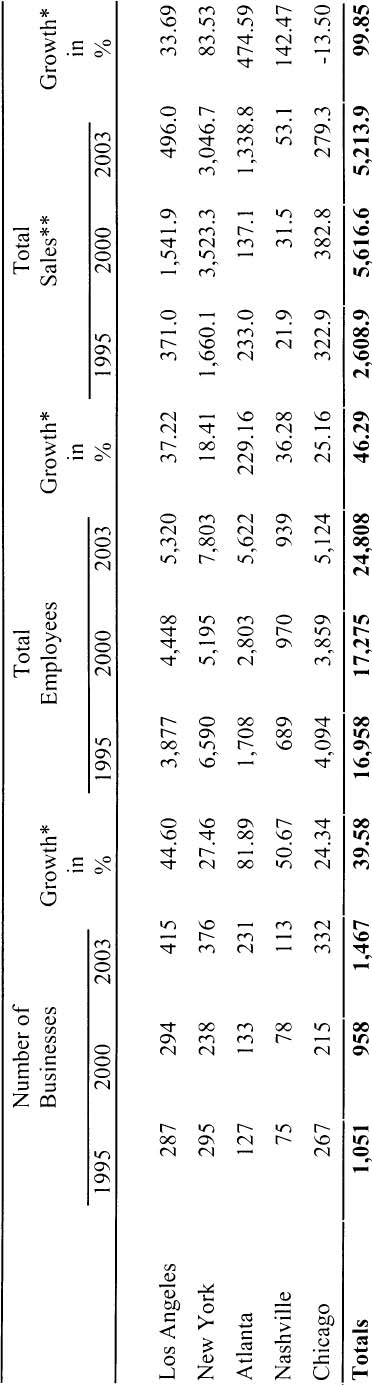

The sector of broadcasting services (table 9) includes radio broadcasting stations, television, radio time sales, electronic media advertising representatives, radio advertising representatives, radio consultants, radio transcription services, music distribution systems, and specific format radio stations. Broadcasting services was the most prolific industry sector of this study generating about one third of the five cities’ total dollar output from 2000 to 2003. Although the percentage growth figures for the group are essentially equivalent to those found in the creative services sector, examination of the broadcast sector’s individual year data indicates uneven growth in both number of businesses and total sales. Additionally, individual rankings among the cities were shown to have changed throughout the period of this study.

New York and Los Angeles, the traditional centers of activity for this sector, lost a combined total of $1.5 billion in total sales between 2000 and 2003. Nevertheless, the eight-year percentage growth for these cities showed a net gain. New York remains the unchallenged leader of the five-city group throughout the eight-year period, despite uneven growth across all three categories, by generating over half the total dollar output for the group. In contrast, Los Angeles’ steady positive growth in number of businesses and total employees was overshadowed by significant fluctuations in total dollar output, losing over one billion dollars in total sales from 2000 to 2003.

Chicago, traditionally perceived as the third-largest broadcast center, has experienced uneven growth in number of businesses and number of employees, and negative growth (-13.5%) in total sales since 1995. Despite its significant percentage growth in number of businesses (50.67%) and total sales (142.47%), Nashville remains in last place among the five-city group. However, Atlanta’s growth in this sector is remarkable as the only city of the group to experience constant growth over the eight-year period. It registered the highest percentage growth of the group in all three categories. Atlanta’s growth of 474.59% in total sales was sufficient to move it from a fourth place position in 1995 to second place by 2003.

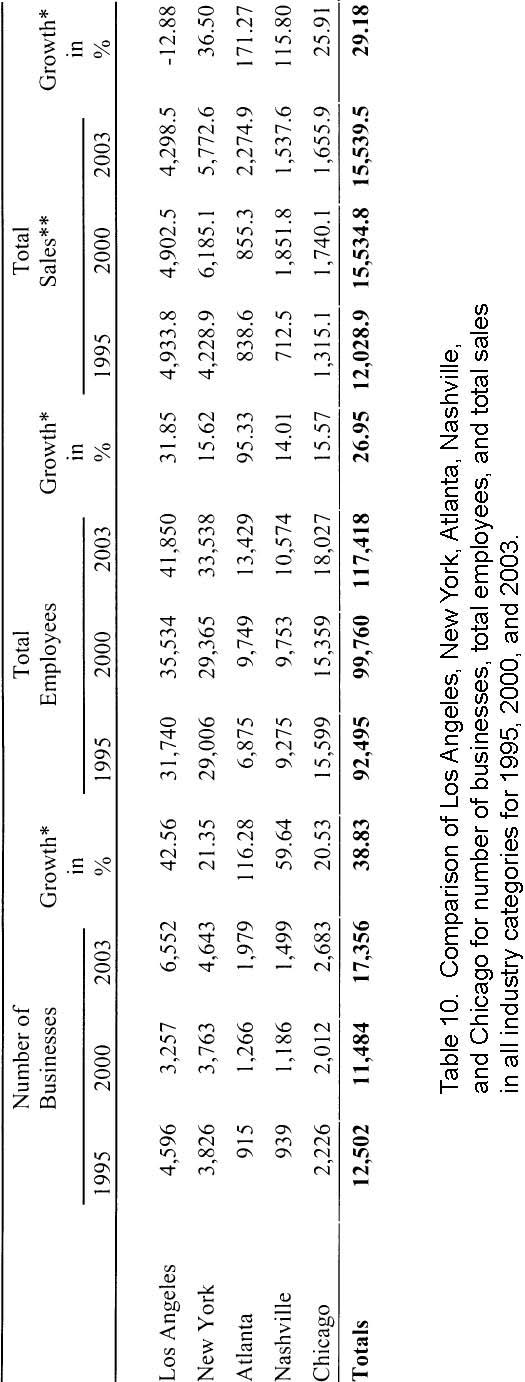

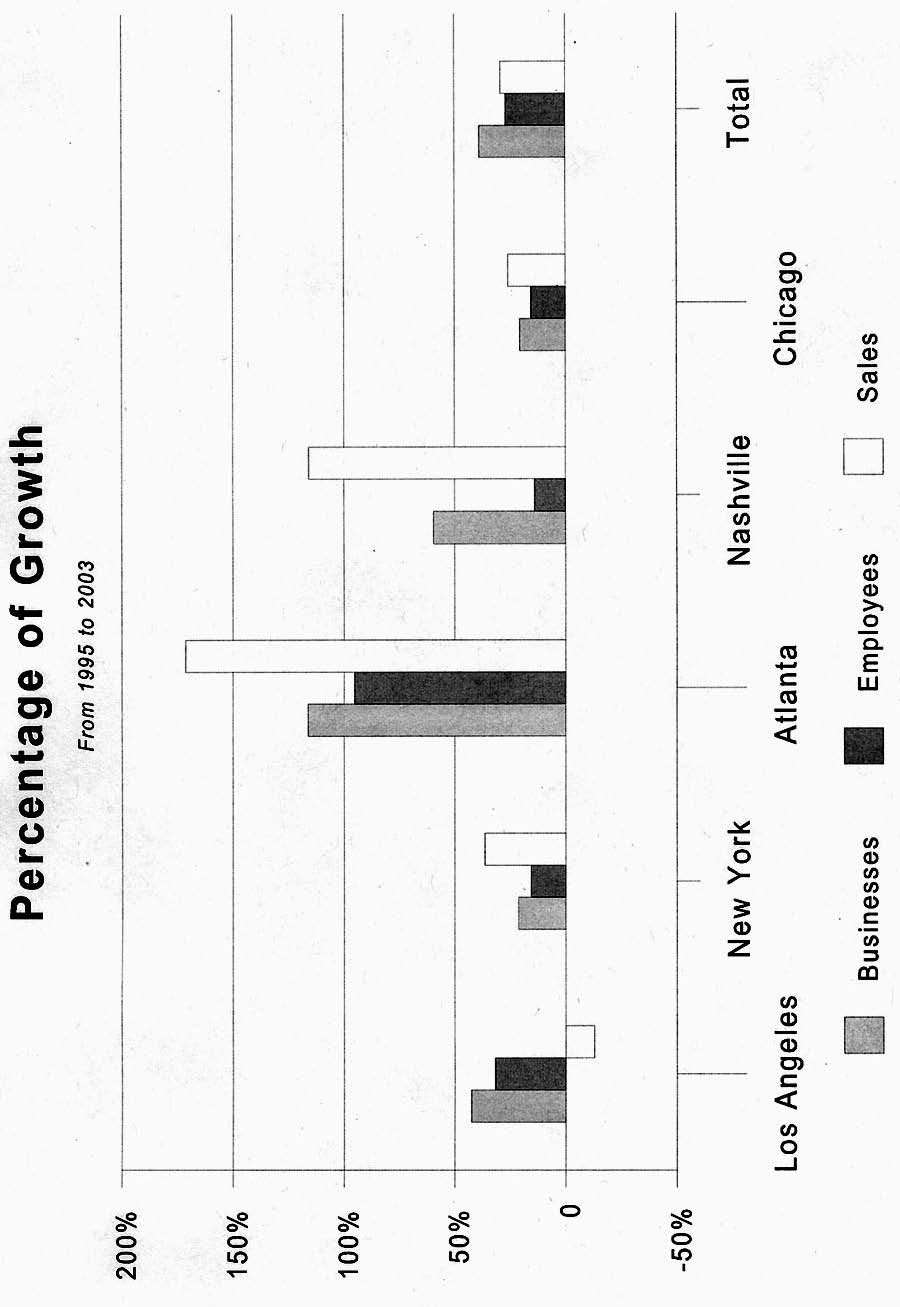

Table 10 contains the totals of the nine sectors of this study. The data indicate that New York and Los Angeles are the most prominent music industry centers in the United States. However, these results indicate that preeminence is less than permanent. Los Angeles, which boasted the larg-est number of businesses and total sales in 1995, lost market share to New York in the ensuing years.

The totals for the five music industry capitals in the categories of number of employees and total sales show positive growth over the eight-year period (26.95% and 29.18% respectively) with the number of businesses showing uneven growth (38.83%). However, with the exception of Atlanta, the cities did experience a decline in total sales between 2000 and 2003. Additionally, Los Angeles has seen a negative growth in total sales (-12.88%) over the eight-year period. Finally, Los Angeles, New York, and Chicago experienced negative growth in number of businesses from 1995 to 2000.

The data indicate that Atlanta was the only city in this study to experience positive growth in all three categories from 1995 through 2003. Additionally, Atlanta garnered the largest percentage growth in number of businesses (116.28%), number of employees (95.33%), and total sales (171.27%). Finally, Atlanta has risen from a distant fourth to an uncontested third place among the music industry capitals in total sales. A discussion of the results of this study is presented in the following section.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that the music industry capitals experienced positive growth in all three business categories from 1995 through 2003; however, significant shrinkage in total sales did occur between 2000 and 2003, indicating the possible presence of the currently reported U.S. music industry downturn. Nevertheless, the record industry’s decline in sales was sufficiently compensated by growth in the other eight industry sectors to give Los Angeles, New York, Chicago, Nashville, and Atlanta an average annual growth rate in sales of 3.65% for the eight-year period. Additionally, the current industry economic downturn was likewise shown to have impacted both the individual cities and the industry sectors in varying degrees, providing strong evidence of trends which include industry decentralization on various levels.

The record industry, the largest of the nine sectors in all three categories, lost sufficient sales by 2000 to be surpassed by the broadcast sector for the five city group. This apparent shift provides a number of opportunities for the other music industry sectors that may no longer view themselves simply as record label support entities. For example, the broadcast sector is undoubtedly contributing to the substantial positive growth in the licens-ing, royalties, and publishing sector through providing increased revenues in performance royalties. Additionally, broadcast sector decentralization is exemplified in the decline of Los Angeles and emergence of Atlanta as this nation’s second radio broadcast center. Industry inter-sector consolidation may also be occurring. The dramatic increase in Nashville’s publishing revenues, combined with New York’s and Los Angeles’ losses over this eight-year period, indicate a possible combining of services to increase sector productivity.

External factors in the current music industry decentralization process include:

1) Federal Communications Commission (FCC) deregulation policies in radio broadcasting; 2) Internet file sharing; 3) varying business climates among the music industry capitals; and 4) technological advancements in audio recording.

The FCC’s intent to facilitate greater local ownership of radio stations and increase revenues from local broadcast is indicated in the results of the study. The record industry’s reaction to Internet file sharing is a salient example of its historic behavior to maintain a static business state. Intra-label disagreements persist as to how to offer customers product via the web as external business entities forge innovative models for such product delivery (Mix, 2003). The varying costs of doing business among the five cities include such items as local taxation, legal restrictions, union regulation, real estate costs, etc. Naturally, an industry sector dependent solely on any one city or region is more vulnerable to shifts in this area than a more nationally diverse model. Finally, recent advancements in professional format audio recording technology have become both affordable and user-friendly to the average musician (Terrell, 2000). Though the aforementioned will continue to negatively impact the high echelon recording facilities on a worldwide basis, the studio sector’s loss will be the gain for the record industry. Artists will again, as in the 1920s (Malone, 1968), be able to submit recordings of sufficient quality to a record label to permit immediate distribution of product. This will save hundreds of thousands of dollars per project in studio costs to both the labels—who previously would have to front this cost to the artist—and the act, who is obligated to repay the label via record royalties. This reduction in overhead cost for the labels provides opportunities to increase productivity and free up capital for investment in, for example, emerging entertainment media.

Decentralization of the music industry will precipitate a number of shifts in its current structure and operations. Among the most visible changes will include the decline in prominence of the traditional music industry capitals such as Los Angeles and the emergence of a larger number of regional centers of industry commerce such as Atlanta. Finally, decentralization will negatively impact industry-wide efficiency in, for example, the areas of business communication and coordination but it will also make the industry, as a whole, more impervious to economic downturns caused by regional and local external factors.

The impact of Internet file sharing, though significant, is not the singular cause of the recording industry’s decline in sales. Competition with other entertainment media such as video games and movies has become increasingly apparent as the labels struggle unsuccessfully to find a successor to mega-artists such as Michael Jackson. The recent U.S. recession has also shrunk the average family’s entertainment budget. However, the authors of this study believe a factor internal to the industry is also negatively impacting sales. The industry’s apparent unwillingness to offer baby boomers (traditionally the largest segment of the record-buying population) with little more than simple reformatting of catalog popular music is, we contend, easily remedied. We propose that the industry redouble its efforts in the area of artist development for this segment of the population. Finally, we must go on record with our support of the RIAA’s current efforts to enforce U.S. Copyright laws. We believe these actions will help stem the tide of Internet file sharing—a necessary protection for the continued health of the record industry. The RIAA’s actions also demonstrate support and respect for individual creative property.

In summary, the record industry’s function as the traditional wellspring of commerce for the music industry seems to be waning. The dominance of the major record labels may be replaced by a more diverse multi-media-based music industry. Additionally, as the music industry continues to decentralize, Atlanta, and as well as other cities, will rise to prominence. Houston, for example, is benefiting from Clear Channel’s success. Put simply, the music industry is not declining; it is simply growing by decentralization. According to the article “Music Industry Welcomes Back the Sweet Sound of Sales” (DSN Retailing Today, 2004), Nielsen Soundscan announced that sales of CDs in the first six months of 2004 were seven percent higher than the previous year. The increased sales were due to strong new releases (Outkast, Norah Jones, Usher, Limp Bizkit, Dave Matthews, etc.), lower CD prices, and digital downloads. Apple iTunes and Roxio’s new Napster have proven that people will pay for music online if it is affordable, easy to use, and a pleasant user experience. DVD sales increased significantly during the third quarter of 2003, with 270 million DVD software units shipped to retail (NARM, 2003). This is a 40% increase over the same period in the previous year. Additionally, 6.4 million DVD players were sold to U.S. consumers during the third quarter of 2003, a 36.5% increase over the same period a year earlier. Experts predict that digital downloading will grow over the next five years. They estimate downloading will generate $270 million in sales in 2004 and become a $1.7 billion dollar business by 2009, but that it will not take the place of in-store CD sales. If the findings of this study are representative of the U.S. music industry in general, the future looks bright (Desjarding, 2004).

Implications for Music Industry Education

If the patterns of decentralization found among the music industry capitals in this study are reflective of nationwide trends, music industry educators must begin to prepare students for more than just two specific professional career tracks (i.e., working for a major record label or engineering in a high echelon recording facility). To this end, music industry programs should offer opportunities for internship positions on a regional and local basis. Additionally, students must be taught entrepreneurial skills and how to employ lateral movement strategies to achieve ultimate career goals.

The development of regional and local internship positions must begin with a search to determine the number and types of music businesses in one’s area. We recommend Dunn & Bradstreet’s MarketPlace CD as an excellent source for this type of information, as well as the reference or music librarians at local universities. Anecdotally speaking, we have found a high level of interest in internship placement from regional music businesses. These firms often employ graduates of music industry programs and seek additional interns.

The development of entrepreneurial skills for music business majors must be an essential component of the educational experience. To accomplish this, entrepreneurial theory and application should be included in the curriculum and internship positions should include as many sectors of the industry as are practically available in an area. Additionally, given the current state of the music industry, the prospect of starting an independent record label should be presented as a valid endeavor to the music business major. Also, incubator music public relations, promotions, marketing, manufacturing, legal, touring, video, and other music related industries need exploring.

Engineering and production majors must likewise be encouraged to develop entrepreneurial skills and take internships at local and regional project studios. It is in this environment that students learn a variety of skills that include the crafts of writing and producing everything from jingles to sound effects, foley production, and production of sound tracks for digital gaming, television, and film scoring. Put simply, the more our engineering graduates can offer a potential client or business, the greater their perceived value, marketability, and survivability.

Finally, all music industry majors must be taught the advantages of lateral movement within the industry. Seasoned music industry professionals contend that a diverse background generally translates into career longevity due to greater industry-wide networking capacity and the ability to sustain employment during industry fluctuations. In a decentralized business environment professional versatility is an essential attribute for survival and success. As educators, we have an obligation to teach students how to thrive in this continually evolving industry.

Table 1. Comparison of Los Angeles, New York, Atlanta, Nashville, andChicago recording studios for 1995, 2000, and 2003.

* Percentage figures compare 1995 with 2003.

** Sales figures are represented in million dollar units.

Table 2. Comparison of Los Angeles, New York, Atlanta, Nashville, andChicago artist’s and entertainer’s managers or agents for 1995, 2000,and 2003.

* Percentage figures compare 1995 with 2003.

** Sales figures are represented in million dollar units.

Table 3. Comparison of Los Angeles, New York, Atlanta, Nashville, andChicago bands, orchestras, actors, and other entertainment groups for 1995, 2000, and 2003.

* Percentage figures compare 1995 with 2003.

** Sales figures are represented in million dollar units.

Table 4. Comparison of Los Angeles, New York, Atlanta, Nashville, andChicago record and prerecorded product outlets for 1995, 2000, and2003.

* Percentage figures compare 1995 with 2003.

** Sales figures are represented in million dollar units.

Table 5. Comparison of Los Angeles, New York, Atlanta, Nashville, andChicago musical instrument stores for 1995, 2000, and 2003.

* Percentage figures compare 1995 with 2003.

** Sales figures are represented in million dollar units.

Table 6. Comparison of Los Angeles, New York, Atlanta, Nashville, andChicago musical instrument manufacturers/wholesalers for 1995, 2000,and 2003.

* Percentage figures compare 1995 with 2003.

** Sales figures are represented in million dollar units.

Table 7. Comparison of Los Angeles, New York, Atlanta, Nashville, andChicago licensing, royalties, and publishing services for 1995, 2000, and2003.

* Percentage figures compare 1995 with 2003.

** Sales figures are represented in million dollar units.

Table 8. Comparison of Los Angeles, New York, Atlanta, Nashville, andChicago creative services for 1995, 2000, and 2003.

* Percentage figures compare 1995 with 2003.

** Sales figures are represented in million dollar units.

Table 9. Comparison of Los Angeles, New York, Atlanta, Nashville, andChicago broadcast services for 1995, 2000, and 2003.

* Percentage figures compare 1995 with 2003.

** Sales figures are represented in million dollar units.

* Percentage figures compare 1995 with 2003.

** Sales figures are represented in million dollar units.

L NYA N C L NYA N C L NYA N C

References

Baskerville, David. Music Business Handbook and Career Guide (7th ed.). Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sherwood Publishing, 2001.

Clark, R. “Radio! Radio!” Mix, 27 (6) (May, 2003): 94-96.

Davis, Clive and James Willwerth. Inside the Record Business. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1975.

Desjarding, Doug. “Music Industry Welcomes Back the Sweet Sound of Sales.” DSN Retailing Today, 43 (16) (August 16, 2004):11-13.

Dunn and Bradstreet. D&B MarketPlace (Version 2.0 CD ROM). Natick, Mass.: Dunn & Bradstreet, 1995.

Dunn and Bradstreet. D&B Sales & Marketing Solutions CD ROM. Natick, Mass: Dunn & Bradstreet, 2003.

Dunn and Bradstreet. MarketPlace CD ROM. Natick, Mass.: Dunn & Bradstreet, 2000.

Fink, Michael. Inside the Music Industry: Creativity, Process and Business (2nd ed.). New York: Schirmer Books, 1996.

Franklin, R. “Manufacturers: Up, Down, All Around.” Mix, 27 (6) (May, 2003): 112-118.

Gelatt, Roland. The Fabulous Phonograph 1877-1977. New York: Collier Books, 1977.

Hall, Charles and Frederick J. Taylor, Marketing in the Music Industry (4th ed.). Boston: Pearson Custom Publishing, 2003.

International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI). Year-end 2003, Statistical Report.

Jackson, B. “A Fine Mess: Dark Days in the Music Industry.” Mix, 27 (6) (May, 2003): 32-41.

Malone, Bill C. Country Music, U.S.A.: A Fifty-year History. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press (The American Folklore Society, 1968), 2002.

National Association of Recording Merchandisers (NARM). Year-end 2003, Statistical Report.

Read, Oliver, and Walter L. Welch. From Tin Foil to Stereo: Evolution of the Phonograph. Indianapolis: Howard W. Sams & Co., Inc., 1959.

Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). Year-end 2003, Statistical Report.

Schicke, C. A. Revolution in Sound: A Biography of the Recording Industry. Boston: Little, Brown, 1974.

Shea, William F. The Role and Function of Technology in American Popular Music: 1945-64. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation. Ann Arbor, Mich.: UMI Dissertation Services, May, 1990.

Shore, Laurence Kenneth. The Crossroads of Business and Music: A Study of the Music Industry in the United States and Internationally. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation. Ann Arbor, Mich.: UMI Dissertation Services, 1983.

Stormant, D. “MarketPlace Analysis Essentials.” Paper presented at the Desktop Marketing in the 21st Century Seminar, Atlanta, May 11, 2000.

Taylor, Frederick J. and Phillip A. Terrell. “A Comparison of Five American Music Industry Centers of Commerce.” Southern Business & Economic Journal, 25 (3 & 4) (Summer/Fall 2002): 244-259.

Terrell, Phillip A. Digital Audio in U. S. Higher Education Audio Recording Technology Programs. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation. Atlanta: Georgia State University, 2001.

Vema, P. “Record Label Remedy.” Mix, 27 (6) (May, 2003): 44-52. Video Software Dealers Association (VSDA). Year-end 2003, Statistical Report. Wadhams, Wayne. Sound Advice: The Musician’s Guide to the Record Industry. New York: Schirmer Books, 1990.

FREDERICK J. TAYLOR teaches music business and popular music courses at Georgia State University in Atlanta, Georgia. He has served as Chair of the Music Industry Department, Assistant Director of the School of Music, and Coordinator of Music Industry. He earned the B.S. degree from Kentucky State University, the M.S. degree from the University of Illinois, and the doctorate from Temple University. He has held the following positions on the MEIEA Board of Directors: Director of Publications, Treasurer, and Director of Composition and Performance. Dr. Taylor is an active member of NARAS, MENC, ASCAP, BMI, NASPAAM, and MEIEA. He has several years of professional experience in the music business as a performing musician, arranger, publisher, producer, and writer of radio and televisions commercials, corporate industrials, and independent film documentaries. He is the coauthor of Marketing in the Music Industry published by Pearson Publishing.

PHILLIP TERRELL is Director of Music Industry Studies at Alabama State University. His industry experience includes serving as a recording studio owner/manager and engineer, talent agent, music store assistant manager, touring and session guitarist, and national sales representative for an audio console manufacturer. Dr. Terrell has taught music business and recording technology at Georgia State University, Northeastern University, and Albany State University.

He has a bachelor of music degree from Mercer University Atlanta, a master of music degree from Georgia State University, and a Ph.D. in higher education/music industry from Georgia State University. Dr. Terrell’s research interests are music industry economic impact studies, artificial intelligence applications in digital audio workstations, and jazz guitar history and techniques. His professional memberships include the National Association for the Study and Performance of African American Music Board of Directors, National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, National Association of Music Merchants, and Music and Entertainment Industry Educators Association.